Why we use the word “cannabis” instead of “marijuana”

When one hears the word “marijuana,” many different images and meanings of the word will come to mind — we all tend to think about marijuana differently. Some believe that “good people don’t smoke marijuana” or that marijuana is only for "criminals and thugs." Others view marijuana as a beneficial plant with many medicinal properties and economical uses. For some, it’s just a fun way to kick back and relax, something to partake in socially with friends — much like beer.

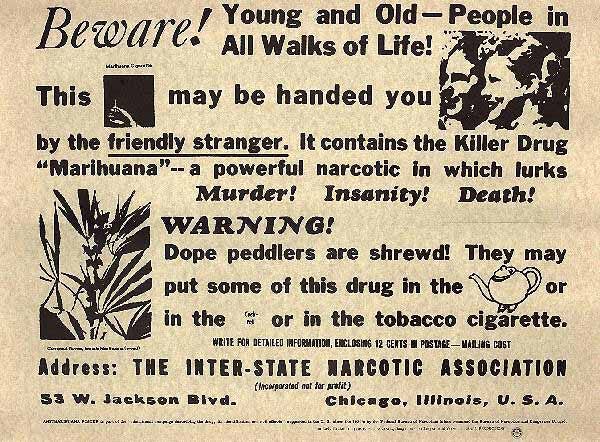

So why are there so many different perceptions of marijuana? It may have to do with generational differences and the types of messaging people were exposed to, specifically messaging that aimed to demonize and discredit the cannabis plant.

What is cannabis?

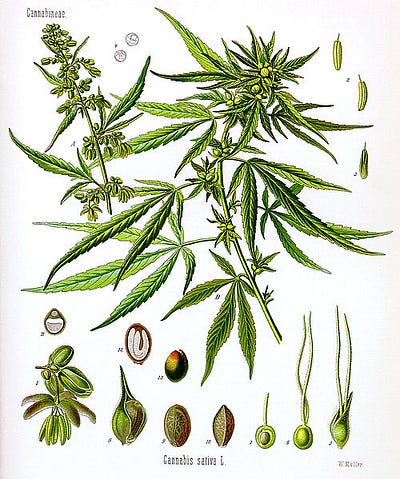

First and foremost, cannabis is a plant (Cannabis sativa). It looks like any other herb or flower — basil, mint, or hops. Cannabis is a genus in the family Cannabaceae, a small family of flowering plants. Cannabis sativa is a species of Cannabis.

While Cannabis sativa is an important source of durable fibers, nutritious seeds, and medical extracts, the plant is poorly understood genetically.

Depending on the taxonomic treatment adopted, Cannabis sativa can include up to three subspecies: Cannabis indica, Cannabis sativa, and Cannabis ruderalis. For our purposes, we modified a simplified nomenclature system based on the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants (ICNCP):

- Industrial Cannabis: Non-narcotic plants, domesticated for stem fiber and/or oil seed. Low Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (less than 0.3% according to US regulation) and potentially high cannabidiol (CBD)

- Recreational Cannabis: Narcotic plants domesticated for high cannabinoids, mostly THC

- Medical Cannabis: Narcotic plants domesticated, contains both THC and CBD

The difference between “industrial cannabis” and “recreational” or “medical” cannabis is derived from two separate genes that are tightly linked and fight to convert the precursor cannabinoid, CBGa, to either THCa or CBDa— the acidic forms of THC and CBD.

When THC production genes are turned “on” and CBD is turned “off,” plants are THC dominant, psychoactive, and are considered recreational. When both CBD and THC genes are turned “on,” plants are moderately psychoactive (as CBD potentially lessens the psychoactivity of THC) and are considered medical. When CBD production genes are turned “on” and THC is “off,” plants are considered industrial.

How and why did people start using the word “marijuana”?

For most of US history, cannabis was legal. In fact, George Washington grew his own industrial cannabis (hemp). An 1862 issue of Vanity Fair advertised hashish candy as a treatment for nervousness and melancholy, “a pleasurable and harmless stimulant.”

“Under its influence, all classes seem to gather new inspiration and energy,” the ad claimed.

In the early 1900s, Kentucky was the greatest producer of industrial cannabis in the US, and into the late 1930s, cannabis was commonly found in tinctures and extracts.

While cannabis was used throughout the nineteenth century in pharmaceuticals and industrially for the fiber, recreational use, or smoking cannabis in cigarettes or pipes, was not widely known or accepted in the US until it was introduced by Mexican immigrants. That introduction, in turn, generated a reaction in the US, tinged perhaps with anti-Mexican xenophobia.

Numerous accounts say that “marijuana” came into popular usage in the early 20th century because anti-cannabis factions wanted to underscore the drug’s “Mexican-ness.” It was meant to play off of anti-immigrant sentiments; hence, enter the “Marihuana” Tax Act of 1937. The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 effectively made possession or transfer of recreational cannabis illegal under federal law.

Then came Nixon, Reagan, and Clinton…

In June 1971, President Nixon declared a “war on drugs.” He launched a massive interdiction effort in Mexico, pressuring Mexican authorities to regulate its marijuana growers. The US government spent hundreds of millions of dollars closing up the border, which only led to reorganization of the international drug trade and proved to be a giant waste of money as Colombia was quick to replace Mexico as America’s cannabis supplier.

In 1973, the Drug Enforcement Agency was created, dramatically increasing the size and presence of federal drug control, and Nixon temporarily placed cannabis in Schedule 1 of controlled substances, the most restrictive category of drugs. He also pushed through measures such as mandatory sentencing and no-knock warrants. Classifying cannabis as Schedule I — a dangerous substance with no valid medical purpose — made it nearly impossible to research cannabis and medical research largely stopped.

John Ehrlichman, a top Nixon advisor, later admitted: “You want to know what this was really all about. The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying. We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Public concern about illicit drug was escalated throughout the 1980s. During Reagan’s first term, the average annual amount of funding for eradication and interdiction programs increased to $1.4 billion, from an annual average of $437 million during Carter’s presidency. Soon after Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, Nancy Reagan began “Just Say No”, a highly-publicized anti-drug campaign. Reagan’s program became known as the “zero tolerance” program, focusing less on education, prevention, and rehabilitation and more on increasingly harsh drug laws and mandatory minimum sentences that disproportionately affected poor people of color. The number of people incarcerated for nonviolent drug law offenses increased from 50,000 in 1980 to over 400,000 by 1997.

Although Bill Clinton advocated for treatment instead of incarceration during his 1992 presidential campaign, he reverted to the drug war strategies of his Republican predecessors by continuing to escalate the drug war with a multi-billion‐dollar annual cost to law enforcement.

President Trump claims he is willing to support a bill that aims to protect states that have legalized cannabis from a federal ban, however Jeff Sessions is threatening to take us back to a 1980's-style drug war.

The “war on drugs” has failed

By making drugs illegal, this country has: put half a million people in prison; instigated violence and death in gang turf wars and overdoses from uncontrolled drug potency and shared needles/AIDS); and eroded civil rightsand enriched criminal organizations.

“Prohibition goes beyond the bounds of reason in that it attempts to control a man’s appetite by legislation and make crime out of things that are not crimes.” — Abraham Lincoln

The “war on drugs” has failed, and we must consider new solutions. Certain drugs are much more serious than others. For example, every day, more than 115 people in the US die after overdosing on opioids.

An Aclara Research study (Illinois patients, 2017) found that 33 percent of patients on pain prescriptions STOPPED using opioids after using medical cannabis and 92 percent DECREASED the number of prescription drugs taken. Consequently, “Big Pharma” stands to lose AT LEAST $24 Billion or 5 percent of annual Rx sales if cannabis is legalized in all 50 states.

Why perpetuate a word that was created to spread misinformation?

We aim to de-stigmatize cannabis use, starting with reintroducing the terms “industrial cannabis”, “recreational cannabis”, and “medical cannabis” into our vocabulary. We encourage others to stop using the word marijuana and replace their usage of the word with the proper, scientific name cannabis.